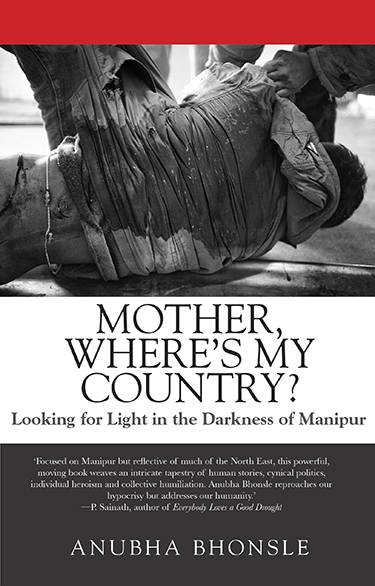

When the unspeakable happens but no one listens: A repressed story of rape in Manipur

Effects of a conflict linger differently on different people. The following excerpt from my book, Mother, Where’s My Country?, is a story of struggle, loss, lack of closure, and denial of memory and justice. The book and excerpt are set in the northeast Indian state of Manipur, a gritty landscape.

When I first started exploring life in Manipur, I wanted to understand the notion of despair here because of the existence of what’s called the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). Since 1980, the act has given security forces unbridled powers—including the authority to arrest and shoot a citizen on mere suspicion and to search property without a warrant. It also protects soldiers from trial and punishment without the sanction of the central government.

The story captures life in a state where midnight raids by security forces are not unusual, although they occur now less frequently than they used to. Children walk to school amid guns while “What to do if you are raped” booklets circulate in markets.

Over the past nine years, I have conducted close to 200 interviews, scrutinized dozens of documents and court testimonies, revisited places and people, and repeated numerous questions. The excerpt here relies on exhaustive interviews conducted over days with two women, whose identities I have protected. These women have broken their silence; we are their witnesses.

***

S would say, “If you carve meat with a dull blade, it’s going to be hard and painful and messy. And a long-drawn affair.” Her friend was right, D thought. This was going to be a long-drawn affair. Just like S’s was.

S was much older but D always thought of her as a close friend. The stout mother of three had a convex belly, like a big bowl, from her difficult pregnancies. D often joked about the long, tight elastic knickers S wore under her wraparound phanek like a corset to hold in the layers of belly fat. The first man who had pinned S to the ground had struggled to remove them. He had cut them open with his penknife and with them, her belly. The gash wasn’t deep but it was long, running from her upper abdomen, where the tight knickers started, to her navel and almost cutting down to her vagina.

S had been conscious through it all; she had fought them in the first few moments, clawing at them. Two had watched, laughing and egging the one on top of her. S had shouted, using all the strength in her veins to move and get his weight off. But he had sunk into her, like a boulder, his hand on her face, sealing her mouth. Barely a squeak escaped her. Even as she caught the rhythm of her breathing after he was done, another one was on her. The second, she remembered, had used her phanek to clean himself. The faces were blurred; in fact, S never believed she saw any of them clearly. She had shut her eyes tight through it all, as if that would be enough to defeat them, make them disappear. But every now and then the outline of a jaw swam before her eyes, or a pair of shadowed eyes, mostly when she took a bath and her hands ran over the faint remains of the scar on her belly. It was a scar of defiance, but it was fear that had become the central thread of her life. S hadn’t told a soul. But the remnants of that day lived inside her like a tumor.

Some evenings D would accompany S as they went shopping for vegetables to the market. At the Ima market, as in many other bazaars in the city, women sat and sold their produce. It was like a fair, chattering women-sellers would call out to buyers, asking them to smell the fish, caught just that morning from the Loktak Lake. Everyone knew everyone here. Housewives bargained and lifted fish, alive and silver, from big tubs. Fish of all kinds came here, the big and small, the almost alive, and the peacefully dead. The silver scrapings turning dark grey littered the ground. While S bought fish, D would sometimes eye the other corner of the market where silk stockings hung and perfumed cosmetics and goods from Myanmar were sold. It seemed like two ends of the world. The concentrated stench of life, the sharp, sour smell of vegetables, fish, fruit and sweat, thinned out at the far end of the market and soft, powdery smells filled the air. As S examined the fish, D would often walk to the other end to luxuriate in the pleasant whiffs of potions and powders. It was on one such evening that S overheard that two people from a human rights group were expected in their village the next day. They were coming to talk to women who had been victims of abuse or torture. In this part of the world the presence of human rights groups or armed groups wasn’t unusual, but it did generate fear and suspicion and there would be whispers but only for a few days, and then people forgot. Violence was generally expected here, and accepted as almost inevitable.

Later that evening, after they returned from the market, without any preface, S told her young friend D her story.

The next morning, the Nambul was flowing as it always did, silent and smooth, but something had changed for S. After the children had gone to school and the man for business, she walked to the market on the banks of the river. She had decided she would meet the human rights team and ask them to come home. D wasn’t sure what this would achieve, so many years later. But S was insistent. “Sorrow is better than fear,” she told D. “And I have lived with both.”

When they arrived, D remained outside, sitting in the courtyard. Inside, S quickly made cups of red tea. The two human rights workers were young, perhaps of D’s age, a man and a woman, both in jeans. They had left their shoes outside and walked in to S’s house carrying sheets of papers and a diary each under their arms. S had shown them to the brown sofa, flipping the cushions to hide the foam peeking through small tears in the velvet cover. But they had avoided it, instead picking up the bamboo stools lying in a corner. The woman had put her diary on the floor; the man had put his on his lap

S sat a little distance away. She hesitated for a while, unsure of how she was going to begin, or even why she wanted to do this and how far this could go. Outside, D could hear her half-hearted chatter with the two youngsters: how she had often told her husband that the door needed repair but he ignored her.

It was the young woman who broke the hum of casual conversation, leaning forward and asking S straight, “What happened and when? Tell us everything.” The young man had his pen ready.

“It was long ago,” S began. “My first son must have been two or three years old—1990, I think, or 1991.”

The young woman and man looked at each other from the corner of their eyes. Perhaps it was already clear to them that something that had happened so far back was going to be useless unless there were specific details. But they did not stop her. In the 1980s and early ’90s, army and police operations were frequent in all of Manipur. So were ambushes, midnight knocks, taking away of men, ransacking of homes. Sometimes men draped in heavy woolen shawls, hiding guns, would ask for shelter. There was no choice; the women of the house then cooked for them. Security forces on search and combing operations would put cross marks on doors to indicate the houses had been searched, lest another group of soldiers come for the same purpose. S had been witness to many knocks and had opened the door many times to armed personnel in search of members of underground groups. Many nights on hearing gunshots they would all duck and lie low.

It was on one such night that the unspeakable had happened.

“No one was at home. There was a knock, many men came inside and searched around, using the butt of their rifles to knock pots and pans, throw off the bedding. They searched every nook and corner, their mud-soiled boots stamping the floor. After a few minutes of mayhem they went away, just as they came.”

Barely a few minutes passed, S said, she had only just locked the door, when there was another knock and three men were at the door

“Were they part of the same group?” the young woman asked.

S wasn’t sure. Once again, D, sitting outside, wondered why her friend was doing this. S was thinking the same. As she spoke, sadness and pain overwhelmed her. She stared at the floor, but continued speaking, recounting all she remembered.

S offered to show them the scar. They politely declined, saying it was not needed and maybe they should all take a break. The two of them went outside. Perhaps they wanted to confer as to what this would achieve. Yes, she remembered details, but she knew no names, no ranks, and no faces. For a moment S sat still in that room, alone, she wanted to tell them more. Veiled by the distance of time her memories had come out as bare-bone notes. “It simply wasn’t ‘meaty’ enough,” the young man said to his colleague. A few months into the underrated and painstaking work of documentation he was certain there wasn’t enough here to classify this as a violation. This was not even documentary evidence, forget courtroom testimony.

S came out of the room, into the courtyard, part cranky, party angry, saying in the loudest tone she had used so far, “I am not tired. I wasn’t even when the three of them pounced on me.”

The human rights workers came back into the room and took their seats again, but S recoiled from the memory now. This was common too; whenever victims went back to a dark place they had been unable to escape, anger followed. Doors were shut, people walked away. Sometimes they returned to complete their stories; sometimes they did not. The young woman and man collected their belongings and left. They broke for lunch at a nearby rice hotel and discussed what they had got.

Almost as soon as they had left, S realized the enormity of what she had done, and she began to cry, and laugh.

S’s case never reached closure. Later, S admitted to D that she didn’t expect it to. Simply raising a voice would not shatter the inhuman silence at the other end, where brute power lived. And yet, pain, violation, fear had to be articulated coherently. After your name, village and the date of the incident, you had to recount the act clearly, the clearer, the better. You could leave out details of how the day started or how you were feeling that day. The act was important. The uniform, your clothes, physical features, marks and bruises, all went into the documentation. Hair pulling, being slammed on the floor, heavy hands shutting out your screams—all were documented. Vaginal wounds too. There was no place in the reports for broken nails or the buckle of a belt that dug deep into your abdomen or the fever that came from a terrible urinary tract infection that lasted for months or the oppressive smell that never left you.

“Haven’t you learnt anything from me? Let’s call the police, tell them all you remember,” S was telling D while gently patting her hair.

“The men who did this will be punished,” she added.

To D that sounded like an afterthought. She turned her face away.

There must be time for sorrow to spend itself, D thought, before it can overcome fear.

(Excerpted with permission from Mother, Where's My Country? Looking for Light in the Darkness of Manipur, Anubha Bhonsle, Speaking Tiger Books)

More articles by Category: International, Violence against women

More articles by Tag: Rape, Sexualized violence, Asia, Trauma