‘India’s Daughter’ offers the first real challenge to India’s rape culture

Public thought in India, as in much of the world, is groomed by the media. And for the purposes of the press, rape is sex and sex sells—with high decibel views and round-the-clock coverage of shocking crimes against young women, preferably in Delhi.

British filmmaker Leslee Udwin's documentary film, India’s Daughter, about the infamous “Delhi gang rape,” the brutal attack on a medical intern that took place on a moving bus the night of December 16, 2012, fell into this comfortable rape protest culture with a splash by showcasing of the brutal thoughts of the victim-blaming rapist and his lawyers. Our government, which is keen on India looking good, banned the documentary. Indian feminists—at least the talk show variety—supported this censorship indirectly by calling for “restraint” through a delay of the documentary’s airing.

Everybody and his or her cousin has a strong opinion on this one.

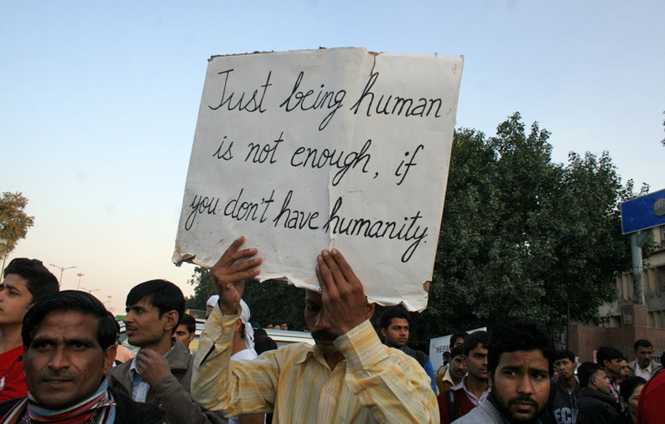

The “casual inhumanity” revealed by the Delhi gang rape “is too uncomfortably familiar to allow it to be visible,” the author argues. (Ramesh Lalwani)

Kavitha Krishnan, a noted women’s rights activist who regularly appears on TV, recommended restraint in showing this documentary while the rapist’s appeal in the Supreme Court was pending, though not an outright ban, so as to prevent media influencing justice. (Interestingly, Krishnan has also been vocal in the opposite direction: She didn’t oppose the trial-by-media in two prominent rape cases in 2013. Both were judged in the media well before any police complaint was filed.)

In India, media cannot name a rape survivor by law, unless explicitly allowed by the survivor. You also can’t discredit a survivor’s testimony without evidence to the contrary. These are meant to be protections for rape survivors who often face social stigma or a trial replete with character assassination. When trial-by-media applies these rules to a rape accusation, you can have pretty alarming results with an anonymous victim making accusations against a public figure, unquestioned. The cases brought to the media first and are judged well before a police complaint is filed.

Putting serious crimes on trial through media discussion is not unique to India, nor is it new. Yet there are actual consequences to doing such a thing—for not only the victims and the perpetrators, but for our own conception of what justice should be. When justice has utterly failed, the press can play an important role in bringing this to light. But oftentimes the media’s motivations are more shallow: Can highlighting a particular case bring high ratings? It is time to examine what such exhibitions of extreme justice do to the women’s rights movement, and the fight against a pervasive rape culture. What happens to the social perception that women rarely receive justice when television clearly tells us that a man should be “in jail for life,” even if he is denying the crime and the woman didn’t even file a police complaint—as has happened—and the police actually arrest him regardless? And, on the other side, what are the consequences when talking heads jump on the government bandwagon in supporting the censorship of a film that illuminates the disgusting attitudes of men who commit violence?

In the case of India’s Daughter, the criminals have already been convicted. So why has the government chosen to censor it, and why are some quarters of the media supporting such a ban? The government claims that parts of the film “appear to encourage and incite violence against women.” Would allowing the film to air sway public opinion truly? Or is the government more concerned with covering up a national embarrassment?

While only some people want to shut down the film altogether, I’d argue that every single person is struck dumb with a complete loss for words when a rapist simply states “she asked for it,” as one does in this film. We have no reply to that statement, though plenty of anger for it. This is where we are in our fight on rape. So how do we move past this moment of censorship and astonishment and make actual progress in the fight to stop violence against women?

***

While the media debate on India’s Daughter began raging, a mob of thousands broke into a jail in distant Dimapur in northeastern Nagaland and, after “overpowering” security, dragged out a “Bangladeshi Muslim” (he was, in fact, not Bangladeshi) accused of rape. The mob paraded him around naked then lynched him. (“Bangladeshi infiltrator” is a common excuse for violence against Muslims in northeastern India.)

Krishnan, who had recommended restraint while the appeal was under trial but not an outright ban on eventually airing India’s Daughter, implied that the faraway violence was because of the documentary. In actuality, the violence was premeditated and had been brewing for days and had nothing to do with it.

Most who take up the cause of fighting rape outside the legal system are usually concerned with an agenda that has nothing to do with preventing further violence against women or even justice.

The public uses a woman’s rape for various purposes. Allegations against famous people are great for a trial-by-media. A communal agenda for violence is a reason for justice by mob lynching. The Delhi gang rape was used for discrediting the then-government. A steady stream of rapes and gang rapes persist, yes, but with that comes little interest by much of society in the fact that women face multiple other kinds of repression in the public sphere.

Media stylizes rape into a dramatic, unheard-of horror that needs stricter and stricter punishments and wider and wider definitions; they say it destroys a girl forever—ignoring the fact that this is a country in which marital rape is legal (unless you’re stupid enough to sodomize her and get caught for “unnatural sex”). Domestic violence laws can send you to jail for beating your wife, but not for raping her; in fact, denying your husband sex is considered “cruelty.” You can engage in legal pedophilia with a girl under 18 if you marry her first. The shock-and-horror zero tolerance for rape rhetoric misses these nuances to violence against women. There are women you meet daily who suffer marital rape who will never merit a talk show or candlelit protest—and they will continue to live with their rapist.

Conviction rates for rape are low. In many instances, community leaders have enacted “compromise” in the form of forcing a victim to marry their rapist, or judges have refused to hand down convictions in order to prevent “excessive punishment” for the rapist.

But, on the other side, statistics are being unevenly skewed as well.

In India, having sex with a woman with the promise of marriage but not following through with the promise counts as rape and makes up a bulk of legal cases, along with false accusations by disapproving parents of consenting girls (65 percent of all reported cases in Delhi)—something activists rarely focus on. Could it be that they want to make every rape seem nonconsensual so that it doesn’t look like rape is “taken lightly”? It is terrible that this area is so ignored, because educating girls on sex, relationships, and dignity can not only prevent these acts of potentially nonconsensual sex, but leave women and girls more empowered—all while making a substantial dent in the statistics. (Chipping away at the misogyny that prevents women from reporting rape, which would bring up rape stats, is a whole other area that requires ongoing attention.)

Punishment for rape in India used to begin at seven years in prison. Now, it is a minimum of 10 years. In a patriarchal country like India, 10 years for a “mistake”—as Indian politician Mulayam Singh Yadav famously put it—could see judges balking at sentencing for rapes that don’t show long-term harm (injury or trauma) to the victim by the time they are judged in our infamously slow and overburdened system.

There is no easy solution for punishment. What can ever be enough to bring justice for a victim? What can be just enough that our courts will actually implement the sentences properly? Rape culture is not easily unmoored.

***

An unrepentant rapist on death row who has a view of women that basically fits into the definition of slavery, as one of the convicted men describes in India’s Daughter, may seem extreme. Yet he is hardly alone.

Who can forget Congressman Dharamvir Goyat’s chilling 2012 statement? “I don’t feel any hesitation in saying that 90 percent of girls want to have sex intentionally but they don’t know that they would be gang raped.” Meaning: Women who are raped were likely “inappropriately” looking for sex (read: sluts) and got more than they bargained for.

The crazed rhetoric is everywhere.

On March 3, while Member of Parliament Yogi Adityanath was on stage, one of his supporters told a massive Hindu gathering to dig up bodies of Muslim women from graves and rape them.

While outrage over rape is everyone’s recent favorite cottage industry, India’s Daughter has rattled people into looking at just how close to home the problem truly is. And for too many, the casual inhumanity is too uncomfortably familiar to allow it to be visible.

Manohar Lal Sharma, one of the perpetrators’ lawyers in India’s Daughter, has in the past given an interview defending their murderous actions and offering his own despicable views on women. The public response at the time was a resigned disgust. Yet, the same words now immortalized in this “scandalous” documentary—that there is no place for women in Indian society—have led to the national bar council meeting to decide whether they should take action against him and his fellow lawyer, who has said equally hideous things.

In my view, the first symptom of change is turmoil. When the loudest voices against sexualized violence against women have never caused anyone discomfort, it is safe to say that no one thought that their attitudes on women were being challenged. This is the first time that those who knowingly or unknowingly espouse rape culture have been unnerved enough that they feel the need to shoot the messenger.

As strange as it may sound, this may be a good sign.

More articles by Category: International, Violence against women

More articles by Tag: Rape, Film, Asia, Sexualized violence