The urgent crisis of missing Black women and girls

Nearly six years ago, millions of people across the world, including then First Lady Michelle Obama and the pope, participated in the viral campaign #BringBackOurGirls. Orchestrated in response to the kidnapping of nearly 300 young Black girls in Nigeria by Boko Haram, the hashtag sought to bring global awareness to this mass kidnapping. Although many can and did debate the efficacy of this digital campaign, it was heartening to see the world at least appear to care about the abduction of Black girls.

In 2017, activists and concerned community members in Washington, D.C., re-launched the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag in an effort to shed light on what appeared to be an epidemic of missing Black girls in the district. Although several Black girls were missing in the nation’s capital, it was soon discovered these numbers aligned with those from the previous year. The combination of a poorly rolled-out police notification system in D.C. about missing people and a history of neglect and invisibility of missing Black girls formed a perfect storm for a brief, widespread panic about what was happening to Black girls in Washington. As soon as it became clear that there wasn’t a spike in missing Black girls, the media moved on and the viral campaign lost steam. But what of the dozen Black girls who were actually missing? It seemed that too few cared about them. The disturbing trend of Black girls going missing continued without any sense of urgency.

The harsh reality is that an estimated 64,000-75,000 Black women and girls are currently missing in the U.S. Arguably due to pressure from activists and advocacy groups such as Black and Missing Foundation, Inc., which documents and brings awareness to missing Black people, and growing national interest in human trafficking, major news outlets such as CNN ran stories in 2019 about the alarming number of missing Black children and Black women in the United States. Sounding the alarm about the lack of coverage of missing Black children and women, the distinct barriers for Black families reporting missing loved ones (such as widespread mistrust of law enforcement), and the disparate ways law enforcement treat disappearances, mainstream publications shed light on the experiences of missing Black children and women as well as their loved ones. It should’ve been a call for better policies and more social services that center Black girls, but the brief spotlight failed to galvanize a more robust and impassioned response.

The tens of thousands of Black women and girls who are missing include abductees, sex trafficking victims, and runaways. Black women and girls exist at the intersection of racism and sexism, and quite often poverty. These barriers contribute to disparate and poor outcomes in many arenas, including but not limited to health, wealth, housing, education, employment, food security, access to water, and violence. It is therefore unsurprising that Black women and girls would be overrepresented among people missing in the U.S. They are uniquely vulnerable and too easily erased from public discussions about the alarming trend of missing people.

For far too many Black girls, marginalization is ever-present. Every day, poor children of all races and ethnicities fall through a rapidly unraveling social safety net. More likely than their white counterparts to be homeless or in economically unstable households, Black girls may be lured or forced into dangerous situations. Homeless Black girls, whether in shelters or on the streets, as well as those in foster care, are targets for sex trafficking and other forms of violence. Although some Black girls reside in loving and supportive foster homes, quite often Black girls without stable living situations run away from their homes or shelters and unknowingly enter into even riskier circumstances.

African American girls comprise over 40% of domestic sex trafficking victims in the U.S. While running away from physical and/or sexual abuse or economic deprivation, Black girls run into sexual predators preying on their vulnerabilities and capitalizing on the lack of collective outrage expressed when Black girls disappear. Runaways don’t get Amber Alerts, as those are reserved for abductees. No texts or sirens go out when these girls go missing. Quite often, law enforcement categorize missing Black girls as runaways. Consequently, their cases aren’t treated with the urgency given to those of people who have been abducted. They disappear into a faceless mass of missing children blamed for their attempt to escape untenable situations. Systemic failures render Black girl runaways invisible and, more harrowingly, disposable. Their stories remain untold or unfairly chronicled as tales of juvenile delinquency and criminality. Black girls aren’t afforded the protection of childhood innocence.

Even Black girls residing in seemingly stable home and community environments experience sexual violence at higher rates than white girls. Black Women’s Blueprint, an organization that advocates policy centered on Black women and girls, reports that approximately 60% of Black girls are sexually assaulted before turning 18. Even conservative estimates indicate that at least 40% of Black girls are sexually victimized before their eighteenth birthdays. Running away from family situations or communities in which all forms of violence occur is not an uncommon response. The failure to address the pervasiveness of sexual violence against Black girls contributes to their feeling uncared for and unprotected. This lack of care and investment in eradicating sexual violence against Black girls results in a perilous context in which Black girls go missing.

Unfortunately, adult Black women don’t fare much better than Black girls when considering how and why they go missing. Racism and sexism coupled with poverty, transphobia, homophobia, and ableism generate a distinct set of conditions for Black women. As they do with Black girls, law enforcement often classify Black women as runaways. Furthermore, Black women endure higher rates of sexual and physical violence than their white counterparts. They often encounter racist, sexist, and classist barriers when reporting violence and within the very systems and organizations established to support victims and survivors of violence. With few or no options for redress, Black women may feel compelled to leave violent and potentially deadly situations. Disconnecting from loved ones and their communities, they seek safety in a world too often perilous for those barely surviving on the margins.

Black women face disproportionate rates of homelessness and are among a rapidly growing population of sex trafficking victims. Recent headlines unveil stories of a serial predator targeting Black women in the sex trade, a DJ trafficking Black girls and women out of a club in South Carolina, and hotel workers in Louisiana and Georgia aiding sex traffickers of Black women in evading police for years. The levels of complicity, indifference, malicious intent, and carelessness render Black women and girls unworthy of protection. They become statistics without stories.

Last October, three-year-old Kamille “Cupcake” McKinney was abducted from a birthday party in Birmingham, Alabama. Just 10 days later, her lifeless body was found in a landfill less than 20 miles from her home. McKinney’s abduction warranted an Amber Alert and received more local and national attention than most missing Black girls. Whereas McKinney’s story gained some traction in larger conversations about missing children, the tragic story of missing five-year-old Neveah Lashay of South Carolina, whose body was also found in a landfill that same week, did not. The relative silence surrounding Lashay’s disappearance is far more common than the more robust response to McKinney’s abduction. Cases of missing Black girls don’t often come with rewards for information or tweets from celebrities.

Black women may fare worse in terms of awareness and outcry. When news broke last year of an interstate sex trafficking ring in Georgia and Louisiana, some within media and law enforcement emphasized the victims’ complicity and “consensual” participation in the sex trade. The victims were Black women and girls. Although the traffickers and those who aided them eventually faced legal recourse, the victims received very little attention. These Black women and girls remained unnamed, disposable people in a sensationalized story about sex trafficking.

Missing Black girls and women deserve more than biased and infrequent coverage — they need substantive solutions to a multi-pronged problem. One of the many promising practical strategies to responding to missing Black girls and women is the RILYA alert system. Created by Peas in Their Pods, an organization bringing attention to the plight of missing children of color in honor of a four-year-old Black girl named Rilya Wilson, who went missing in Florida in the early 2000s, the RILYA alert system is a more inclusive approach than the Amber Alert system to informing the public about a missing child. RILYA alerts aim to help missing children of color get more media attention whether or not Amber Alert has been issued.

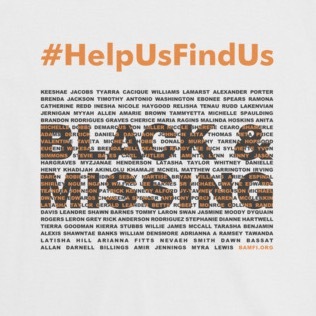

There are also broader, preventative solutions. To address the multitude of reasons Black girls and women go missing requires supporting organizations committed to ending homelessness, overhauling the foster care system, using victim-centered models for ending sex trafficking, centering Black girls and women as victims of sexual and gender-based violence, and fighting for affordable housing and food security for Black families. Tens of thousands of Black girls and women await a more forceful and sustained effort to Bring Back Our Girls. Organizations such as Peas in Their Pods, Black Women’s Blueprint, RAINN, and other underfunded and underresourced groups can’t fix this crisis alone. Their tireless work to fight on behalf of missing Black girls and women is a powerful reminder that those missing deserve more than hashtags.

More articles by Category: Race/Ethnicity, Violence against women

More articles by Tag: African American, Black, Racism, Gender Based Violence, Activism and advocacy