‘Conditions Were Brutal’: The Toll of Two Years of COVID-19 on Women Behind Bars

Two years ago, when the COVID-19 pandemic first swept across the United States, correctional facilities largely ignored public health guidance to decarcerate as many people as possible, as quickly as possible. Although there were efforts for early release of some medically vulnerable people from jails and prisons at the start of the pandemic, and most women are charged with nonviolent crimes like property or drug offenses, those numbers have declined and jail populations have risen again.

“Public health experts have said that the best way to mitigate spread inside facilities is to decarcerate,” said Hope Johnson, a data fellow with the UCLA Law COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project and co-author of the report “Horrible Here”: How Systemic Failures of Transparency Have Hidden the Impacts of COVID-19 on Incarcerated Women. “Other interventions like masking, social distancing, etc., are effective at controlling the spread of the virus — but large-scale decarceration is required to protect public health and prevent mass outbreaks in carceral settings. Instead, facilities suspended visitations and used quarantine, confining people to be alone in their cells for most of the day, except for one hour, having their meals delivered — in effect, solitary confinement. Even though there are policies for emergency release during situations like a pandemic in every state, there is little political will to take the steps to do this. There is a fear of decarceration that is not supported by the fact of who is in prison and for what."

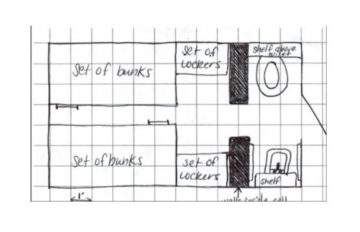

Although all correctional facilities are conducive to the spread of infectious disease, “women are often held in dormitory-style settings, which is especially unsafe during COVID,” said Clinique Chapman, associate director of the Vera Institute of Justice and MILPA’s Restoring Promise initiative, which provides a supportive community for young adults in prison. And facilities are ill-equipped to provide care to the women who get sick. “Prison is not a place to ensure medical care. It is not a hospital, and we should have released more people at the beginning of the pandemic. In order to flatten the curve of the rate of infection, we needed to take care of all our systems, including correctional facilities, in the same way that we addressed infection rates in schools and nursing homes. People in correctional facilities are also members of our community."

Even before the pandemic, women were entering the criminal justice system with a higher prevalence of a wide array of physical and mental health conditions than incarcerated men or the general public. They have higher rates of trauma than incarcerated men, with 86% having experienced sexual violence. And every aspect of incarceration, from the arrest to being detained and held behind bars, is a triggering and retraumatizing experience. COVID-19 “exacerbates all the problems for incarcerated women that were already there,” said Akua Amaning, director of criminal justice reform at the Center for American Progress. “The rise in the use of solitary confinement, which takes a huge emotional toll, is not an adequate way to address the rise in COVID cases.”

The decision to lock down facilities rather than decarcerate has had brutal consequences. “The lockdown started on April 1, 2020, and at first we thought it was an April Fools’ Day joke, but it wasn't,” said a woman who was incarcerated in a federal prison at the beginning of the pandemic. “We weren't let out of our cells for five days straight, no showers, no communication, nothing. There were four of us in a 7-by-12-foot cell. After five days we were let out for five minutes a day to shower, but only three days a week. Then after a few weeks, we could be out for 15 minutes to shower, use the phone, check our email, and get hot water and ice.”

The incarcerated women who work in the prison kitchens were also confined to their cells, so there was no one to cook. “Our meals during this time were what we call bagged nasties — a mix of sliced bread, lunch meats which were slimy, discolored, and fuzzy, cheese and peanut butter, and a package of expired cookies. They gave us each one medical mask that was supposed to last two weeks, which we then had to turn in for a new one. Then we were given two cloth masks but we had to wash them ourselves. We weren’t given any soap or cleaning supplies. We didn’t get to go outside for about five months.”

Since the start of the pandemic, prisons and immigration detention centers have reported at least 592,148 COVID-19 cases at press time, with the numbers only increasing. However, getting accurate information is difficult, if not impossible, as not all facilities are keeping records. The death rate from COVID-19 in prisons is well over twice as high as that of the general U.S. population, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, with 200 deaths per 100,000 incarcerated people, while the rate for the general population was 81 deaths per 100,000 people, by April 3, 2021. “Study after study shows case rates and death rates are higher in jails, prisons, and carceral facilities than in the general population because it’s essentially an impossible place to maintain any of the public health protocols, like social distancing,” said Nancy Rosenbloom, senior litigation advisor at the ACLU National Prison Project.

The lockdowns didn’t stop the spread of COVID, and correctional facilities failed not only in distributing an adequate amount of PPE and personal cleaning supplies, but in providing basic necessities. “There was never clean water to drink and we had to boil it or melt ice to get something better [to drink],” said a woman who was incarcerated in a state prison. “They never provided me with any soap, all the laundry was done by hand and hung in our cells to dry, and [there were] no clean sheets. I struggled to help myself, so I slept a lot.” She ended up getting a severe case of COVID, ultimately falling into a coma, and although she survived, she was left with scars on her lungs. While she was hospitalized, “the nurses hardly ever came to see me. The experience was terrifying and very traumatizing for me, and I am still disabled from COVID.”

COVID policies at the more than 7,000 state and federal prisons, jails, juvenile correctional facilities, and immigration detention facilities vary widely, often dictated by the facility administrators and not necessarily by the Centers for Disease Control guidelines, although most have at least some medical professionals’ input. Some facilities have instituted lockdowns whenever an outbreak occurs. Staff shortages, a chronic problem throughout the pandemic, have resulted in further restrictions. “Because of staff shortages, many people have been spending 23 hours a day in their cells, and in some places have had no outside time for two years,” said Rosenbloom. For women with a history of abuse, being confined behind bars for most of the day is particularly traumatizing.

Understaffing has also meant that some facilities have lowered their hiring and training requirements, potentially resulting in unqualified staff. "When you have staff shortages and more lockdowns, it’s harder for women to get help,” said Jesse Lerner-Kinglake, communications director at Just Detention International, a health and human rights organization that seeks to end sexual abuse in all forms of detention. “We are still getting as many letters from survivors of sexual violence as before the pandemic, but now there are no services inside to provide help. And when our staff has been able to go inside, what we've seen is a community that is completely traumatized and shell-shocked by what they have gone through.”

A majority of incarcerated women are mothers, and most are the primary caretakers of their children. The loss of family visits for large chunks of time during the past two years “propels someone into a depression, so they are like, ‘I’m not going to shower, I’m not going to get out of bed, because my kids aren’t coming.’ We kept mothers from touching their children for a year, and it will definitely impact their relationships,” said Denise Rock, executive director of Florida Cares Charity, which advocates for incarcerated people in Florida. “Video calls are a poor substitute and aren’t like Zoom. They are like something from the 1980s, with lots of static and frozen screens and poor connection.”

When facilities did start allowing visits to resume, they were often under tighter restrictions. At Lowell Correctional Institution, the largest women’s prison in Florida, “the visits were closed down for almost a year, and when they started them again, there was a makeshift plexiglass barrier separating the women from their children and families and there were no hugs allowed or anything,” said Laurette Philipsen, an advocate for incarcerated people in Florida who was incarcerated at Lowell prior to the pandemic.

"It's a tremendous burden on both women and their children if days and weeks go by without communication,” said Mary Price, general counsel at FAMM (formerly called Families Against Mandatory Minimums), a nonprofit criminal justice advocacy organization. “Having that evening call and contact is a huge lifeline for women and a source of emotional support for the family too. Going for weeks without hearing a loved one’s voice in the middle of a pandemic is hard, and frightening. And this lack of communication extended to circumstances when incarcerated people were sick enough to be sent to the hospital. The Bureau of Prisons is obliged to let the next of kin know when their incarcerated loved one is moved to an outside hospital. We heard of a number of occasions where family members were not informed that their loved one had been hospitalized or were only told of their condition by the person's cellmate. This happened over and over again.”

Correctional staff themselves have brought the coronavirus into facilities. “We were blamed for the cause of COVID-19 being spread throughout the prison, but in reality, the first case came from an officer who refused to stay at home because he needed his pay — the prison had no cases until he tested positive,” said a woman who was paroled last year after spending over two decades in a state prison. “We were denied PPE. Only the officers were allowed PPE at first. We were isolated in our cells and not allowed outside for any reason — period. I believe almost a week passed before we were allowed to shower. We were fed inside of our cells, given medication inside of our cells, and there were no phone calls or any interaction with the outside world. We weren’t allowed to see doctors unless it was a serious emergency. Mental health workers refused to do wellness checks in fear of getting COVID-19 through the door.”

There was no laundry service for a while because of a fear that COVID would spread through clothing. “It was mentally, physically, and emotionally taking a toll on each and every one of us. Historically, the institution is known for contaminated water. We were given this water three times a day in our cells by the housing officers. All in all, the conditions were brutal. Being without family communication through visits and regular phone calls was heartbreaking, and a sense of hopelessness fell on me. I don’t think society understands the way women were treated at this time in history.”

By August 2020, 25 states were still not requiring correctional staff to wear masks, and less than a third required incarcerated people to wear them. “If you think about how hard it has been for people on the outside, just imagine how difficult it is for people locked up,” said Rev. Sharon White-Harrigan, executive director of Women’s Community Justice Association, which advocates for women and gender-nonconforming people impacted by mass incarceration. Correctional facilities “became reactionary rather than proactive. So many things went wrong because people went into a panic and it was every person for themselves. We need to look at what we are doing as a society."

In addition to COVID, "our prisons are filled with women who have mental and physical health problems,” said Andrea James, founder and executive director of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. “They are getting chemo or need dialysis or medication, and all of these needs are not being met. We talk to incarcerated women all around the country, and all the stories [of terrible conditions] are the same. There has been a rise in moldy and out of date food being served and religious beliefs are not being upheld, so we have reports of our Muslim sisters being served only a slice of bologna and nothing else, which they can’t eat.”

The loss of family visits “is so painful,” said James. “Not everyone has their children all in one place,” so that makes keeping in touch by phone more complicated. “Video calls are not free, and some places have also cut free phone calls. And for the children who are already dealing with the disconnection of not being in school, it’s very destabilizing. The pandemic laid bare how ill-equipped this country is to take care of not only incarcerated women, but everybody."

More articles by Category: Health

More articles by Tag: COVID-19, Prison, Justice