100 Years After the 19th Amendment, Taking Stock of Black Women’s Political Power

I am a historian with a new book about 200 years of Black women’s politics, from 1820 to 2020: Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. It’s a broad swath of time, and still I often get asked whether anything has changed for Black women in politics since the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment. While too little has changed since women’s suffrage protection was added to the Constitution, I admit, my answer is still a determined yes. Black women have traveled an impressive distance over the last century. And where they are in 2020 suggests they are on their way to exerting outsize political influence this November and beyond.

Oftentimes the question comes to me with a note of skepticism about how far Black women have come: Don’t they face voter suppression in 2020 that parallels that of 1920? To this I have to admit, “Yes.”

In 1920, as the 19th Amendment made its way to ratification, Black women knew that despite federal protection for women’s votes, too many of them in the South would be kept from the polls. Nothing in the Amendment prohibited the states from imposing Jim Crow laws upon Black women voters. Black men already faced poll taxes, literacy and understanding tests, grandfather clauses, and violence when they tried to cast their ballots. After passage of the 19th Amendment, Black women were equally disenfranchised. Such state laws were neutral on their face, meaning that they never said Black women could not vote because of their race or sex. Still, local officials selectively enforced these laws to keep Black women from casting ballots. Intimidation and outright violence on Election Days meant that Black women also chose between life and death when they considered heading to the polls in 1920.

The parallels between the voter suppression of the 1920s and that of today are important. In 2020, some state lawmakers have re-enacted voter suppression laws that are neutral on their face, but discriminatory in their effect. Voter ID requirements, the purging of voter rolls, and the shuttering of polling places all are imposed through the discretion of state and local officials who disadvantage voters of color, including Black women. The same officials hem, haw, and bungle plans for ensuring that all voters can, in light of the pandemic, safely cast their ballots. Black women are among those who will be asked to risk their health and safety when voting. Exercising the right to vote has once again become a matter of life and death, especially for Black and Latinx Americans, whose rates of illness and death from COVID-19 outpace those of Americans generally.

The 2013 gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights Act makes our present moment appear even more like 1920. In Shelby v. Holder, the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the pre-clearance provision of the VRA. This means that today, states that had historically engaged in voter suppression are at liberty to revive such schemes without federal oversight or approval. And many have. It was true in 1920 much as it is true today that individual states operate unchecked as they set in place barriers to Black people’s votes. And this barring of voters from the polls has no post facto remedy — a vote not cast is a vote lost for all time. There are no do-overs in the aftermath of an Election Day, even one tainted by voter suppression.

Why then do I insist that Black women have made important strides in politics since 1920? I point first to the new generation of Black women officeholders that is taking hold in Washington.

Black women in Congress were but a dream in 1920. At that time, too many white Americans remained committed to defending a white man and woman’s republic, one in which Black Americans were relegated to the margins of politics if not excluded altogether. That scheme was thwarted only by Black women who turned out at the polls in states like California, Illinois, and New York even before 1920, proving their commitment to influencing parties and elections. After passage of the 19th Amendment, Black women continued to battle against disfranchisement in suffrage and citizenship schools where they trained one another to face off against recalcitrant voting officials. They headed to registration offices and polling places en masse that year, working together with the sort of steely courage that resisting violence demanded.

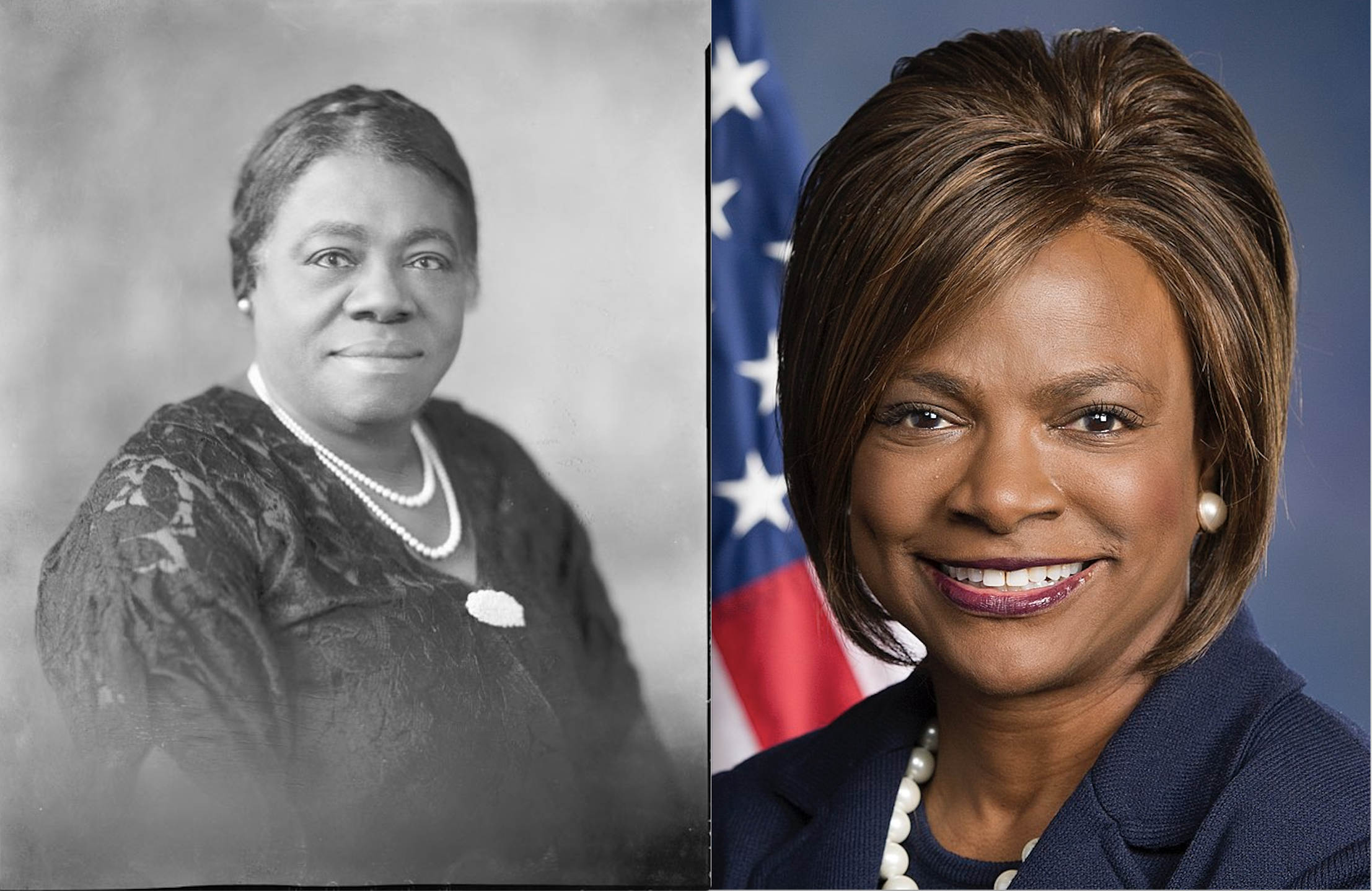

When they were thwarted at the polls in the Southern states in 1920, Black women turned to organizing, drawing together by the thousands. They worked through their oldest political organization, the National Association of Colored Women, founded in 1896. Starting in 1935, the National Council of Negro Women became a new base for political work. Black women used Republican party activism and patronage to grab political power, despite disenfranchisement. Florida’s Mary McLeod Bethune, an educator and voting rights advocate, came to Washington and won the ear of President Franklin Roosevelt. By 1935, Mrs. Bethune was organizing Roosevelt’s Black cabinet and wielding power in the New Deal’s administrative agencies. Too many Black women, including those in Bethune’s home state, could not vote. Still, she used patronage to bring them to the nation’s capital, installing Black women in policy-making positions where they drove resources to communities hardest hit by the Depression.

In the modern Civil Rights era, Black women occupied the front lines of voting rights advocacy, at great risk. Their campaigns waged in the South’s most recalcitrant and dangerous precincts led to brutal confrontations such as that on Selma, Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. There, state officials tear-gassed and beat hundreds, including local activist Amelia Boynton Robinson. Behind-the-scenes organizer Diane Nash made certain that medics were on hand. This was the essential work of voting rights. In Mississippi, Fannie Lou Hamer came of age as a voting rights organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. By 1964, she made herself an undeniable presence at the Democratic National Convention as a representative of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Hamer worked in back rooms and in front of national television cameras, pressing her claim that her state’s all-white delegation was illegitimate, having been chosen without the input of Black Mississippians. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law during a grand White House ceremony, only after Black women had force the question onto the national agenda.

Today, Black women in politics stand upon the shoulders of these early voting rights champions. They drive the outcomes of critically tight races such as that in 2017 Alabama. There, 98% of Black women voters turned out to cast their ballots for U.S. Senate candidate Doug Jones, making the difference in a contest that flipped that seat from red to blue. Those vying for public office were put on notice: Black women will organize to vote as a bloc and then turn out on Election Day. They are a constituency of consequence.

In 2020, Black women are running for Congress in record-breaking numbers. In 2018 they numbered 40 among federal office hopefuls. Americans have come to recognize these newcomers as household names that include Val Demings of Florida and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts. Today, at least 130 Black women are major-party candidates for the House and Senate, according to a report from the Higher Heights Leadership Fund and the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. Black women are converting their electoral power into a force that can also win public office.

Of course, there is no stronger statement about the electoral power of Black women than Joe Biden’s choice of Kamala Harris as the Democratic vice presidential candidate. Among the prospects considered by Biden were a total of six Black women, each with a distinct record. If in 1920 too many Black women were thwarted by those who aimed to exclude them from politics altogether, today they are forceful contenders for an office one heartbeat from the presidency.

The lesson is plain. In the 100 years since the 19th Amendment was ratified, Black women have built upon early work for voting rights, much of it waged in the years after ratification. And still, vigilance is required as new voter suppression laws keep Black women from the polls. Here, the work of Stacy Abrams through Fair Fight and Michelle Obama through When We All Vote continues that tradition, ensuring that all Black women and indeed all Americans no longer confront hurdles when it is time to cast their ballots. This work fuels the likelihood that a growing number of Black women lawmakers will shape law and policy in Washington. A great deal has changed for Black women in politics since 1920. And still there is work to be done.

More articles by Category: Politics

More articles by Tag: Women's leadership, Activism and advocacy, African American, Black, Civil rights, Elections