This New Book Explores Belonging and Being Mixed-Race

For author Kylie Lee Baker, fantasy novels have always been a way to view big issues in approachable ways.

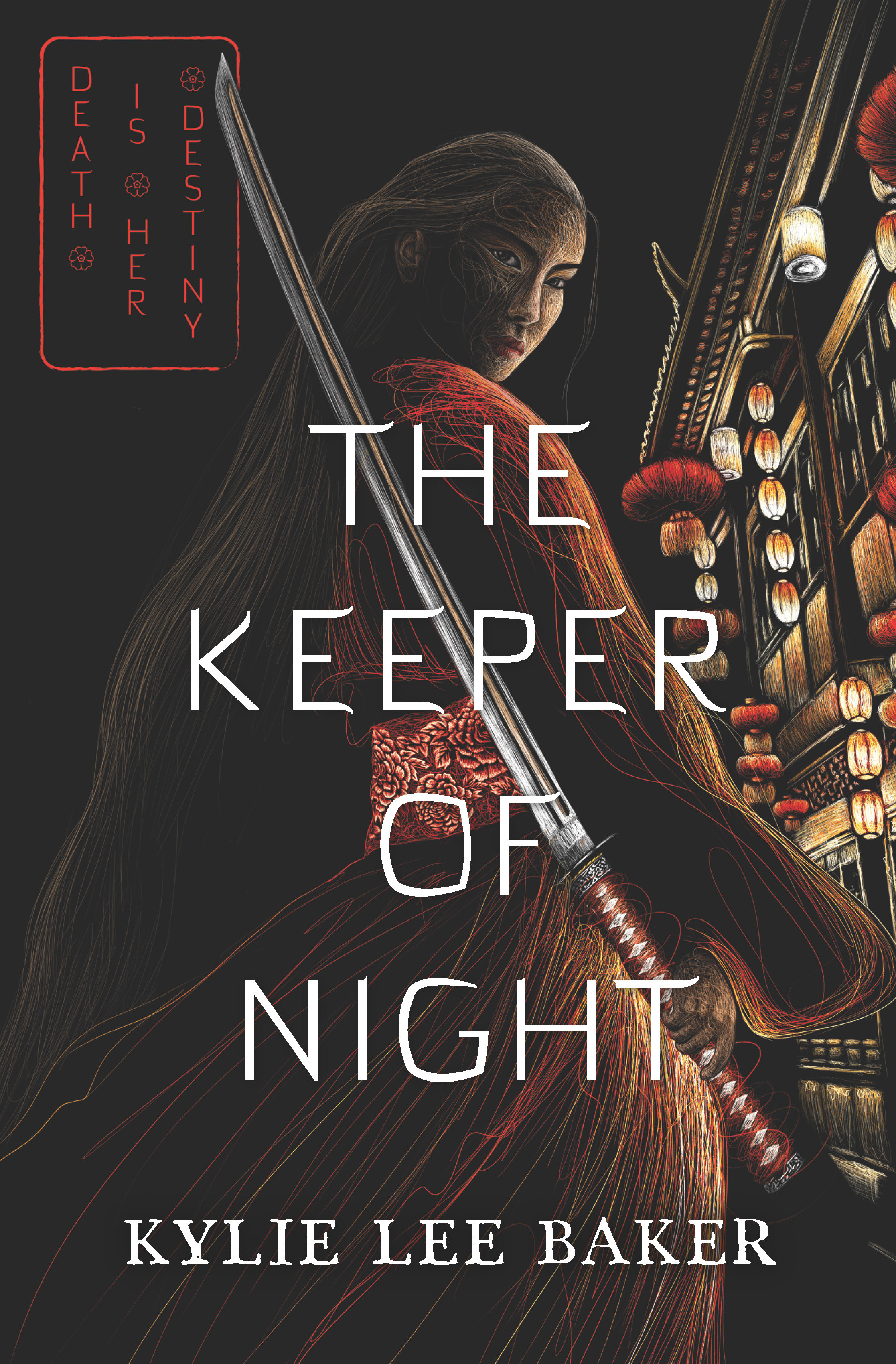

Fantasy “can sometimes feel like a safer, less direct way to confront serious problems,” Baker told the FBomb in an email. While writing her debut novel, The Keeper of Night, released earlier this month by Inkyard Press, Baker knew she wanted to create a story that emulated the “expansive magical worlds” the books she loved as a child were always set in.

The Keeper of Night tells the story of Ren Scarborough, a half British Reaper and half Japanese Shinigami who always feels as if she must find a delicate balance between the two parts of her identity. Coming of age in London, Ren knows her background means she is viewed with suspicion by her fellow Brits, and when she flees to Japan with her younger brother, she finds that things are just as complicated when she tries to navigate Japanese Shinigami society.

We had the chance to chat with Baker over email about creating a story in an alternate 1890s world, her writing process, and what it was like writing a character whose background resembled her own.

The Keeper of Night is set in an alternative 19th century London and sees your main character, Ren, heading to Japan as the story progresses. What was researching both of these countries like, and how did that research appear in your writing?

Unsurprisingly, it’s much easier to find English language resources about 1890s England than Japan, though the scenes in England required comparatively less research. Victorian England is just such a pervasive setting in American media that I never had to pause for questions like: “What does a street in London look like?” because I already know, and most readers can already picture it. The two things I had to research the most were the logistics of taking a boat from London to Japan and bathrooms for a scene when Ren takes a bath. I had to read about plumbing systems, soap, shampoo, etc., and even so, a lot of it is guesswork — it’s not as if everyone bathed with buckets in 1889 and suddenly everyone had pipes in 1890 — a lot of changes were gradual and depended on where in England you lived and how much money you had. I wasn’t too hard on myself, though — I think people would be hard-pressed to take issue with a slightly outdated plumbing system when my book is full of flesh-eating demons.

Researching Japan was harder because I knew I had to be more descriptive — the average American reader has no idea what a street in 1890s Yokohama looks like, so I was basically starting with a blank canvas. I found a decent amount of photographs in digital archives that I relied on to establish the setting. I also read a lot of blog posts from people who had traveled to the different cities in Japan that Ren’s trio visits — it was important to me that each place in the “real world” of Japan felt unique because I think Americans tend to see Japan as a monolithic place. I haven’t been to many of those cities, so I would get a feel for how they are now, then take note of what landmarks there wouldn’t have been constructed yet in the 1890s so I could mentally “rewind” the setting.

How would you define “Shinigami” to those who are unfamiliar with Japanese mythology? When did you realize you wanted to incorporate those myths into your work?

Shinigami are Japanese supernatural creatures related to death in some way, but for the purposes of my book, they basically are grim reapers who can control light. There are lots of different interpretations of Shinigami in Japanese folklore and media — the Shinigami in Death Note (a fantastic anime!) are hideous monsters who live in hell and toy with humans, while the Shinigami in Black Butler are handsome, bureaucratic, scythe-wielding soul collectors. I’ve always been fascinated with death mythology, so I wanted to contribute to this canon by offering my own interpretation. I think any kind of creature who works with death needs to be very sharp and unyielding, and I’ve always been drawn to those kinds of characters.

In many ways, this novel is clearly an allegory for being mixed race. What did you want to convey through Ren, and how did you draw on your own experiences as someone of Japanese, Chinese, and Irish descent to create this character?

The main thing I wanted to convey is that racial purism is an issue everywhere. Ren runs away from England, thinking that Japan will be her oasis of love and acceptance, only to realize that no country is exempt from prejudice. This was an important point I wanted to make in this book because I’ve often been hurt by the way discrimination against mixed Asians is normalized in Asian communities. It’s very difficult for Asian people to speak up against discrimination within our own circles without being accused of being divisive. My biggest hope for this book is that it helps mixed-race teens feel like their struggles are legitimized and that it helps people who aren’t mixed-race have a better understanding of and respect for some of the problems we face, which are different from theirs.

Finally, you mentioned in your acknowledgments section that you wrote a good portion of this book while living and working in Korea. What was that experience like, and do you think writing this book about a journey while you were so far from home yourself influenced how you approached the story?

Living in Korea was a fantastic adventure. Every day there, I felt like my life was a wide-open door where absolutely anything could happen. I taught English to a wonderful group of kids at a school at the top of the hill where you could look down over the whole district. I found a hundred new favorite foods, took rickety buses out to green tea fields, climbed mountains after eating nothing but soju and fish stew, and played in abandoned theme parks. I miss it every day!

However, it was also a very difficult place to live as someone who doesn’t “pass” as Korean and isn’t fluent in Korean. The main reason I moved back to America was that whenever I was in public in Korea, I felt like a foreigner first and a person second. It’s not that Korean people were unkind; it’s just the result of living in a place that’s very racially homogenous compared to where I grew up, where your differences are very obvious. Lots of people move to Korea and don’t internalize this quite as much as I did, but as someone who’s been othered my whole life, having that feeling magnified so much was overwhelming.

I want to be clear that Ren’s experiences in The Keeper of Night are not drawn directly from my time in Korea — Japan and Korea are very different countries, and I don’t want to conflate them or the people in them. However, I do think that living abroad gave me a better understanding of how the word “foreigner” can grow tiresome even when it isn’t intended as an insult, and how hard it can be to be surrounded by Asian people who can’t see you as you see yourself.

More articles by Category: Race/Ethnicity

More articles by Tag: Books